The Etruscan Pyramid at Bomarzo is a relatively new discovery. Two local archaeologists named Giovanni Lamoratta and Giuseppe Maiorano stumbled across it in the spring of 1991. But news of its discovery received little fanfare and it remained unknown to the world. Then in 2008, Salvatore Fosci, a local resident of Bomarzo with a passion for local history, decided he would uncover the Etruscan pyramid. When Fosci’s grandfather served as a sort of custodian of these woods, they called it Sasso del Predicatore (“Stone of the Preacher”) or simply the “Stone With Steps.” The stories his grandfather and father told about the stone inspired Salvatore to find it and clear away the roots and vegetation. In this way, he would make that amazing part of their history accessible to the world.

https://www.historicmysteries.com/etruscan-pyramid-of-bomarzo?fbclid=IwAR3Uj-QbTmKf2iX-0SsKtjjyQAM8GHuVWtyE69wZg4jy0QlndX5EuSxyhCc

Cahokia: The Largest Native American Pyramid North of Mexico

What Does the Etruscan Pyramid Look Like?

Upon first impression, the sloped Etruscan stone monument is reminiscent of Mayan artifacts from the jungles of Belize and Mexico. Although its name suggests the shape of a pyramid, such as those of Egypt, it is technically not a pyramid. The rock is inversely triangulated on just one side, while the rest of the altar displays quasi-right angles.

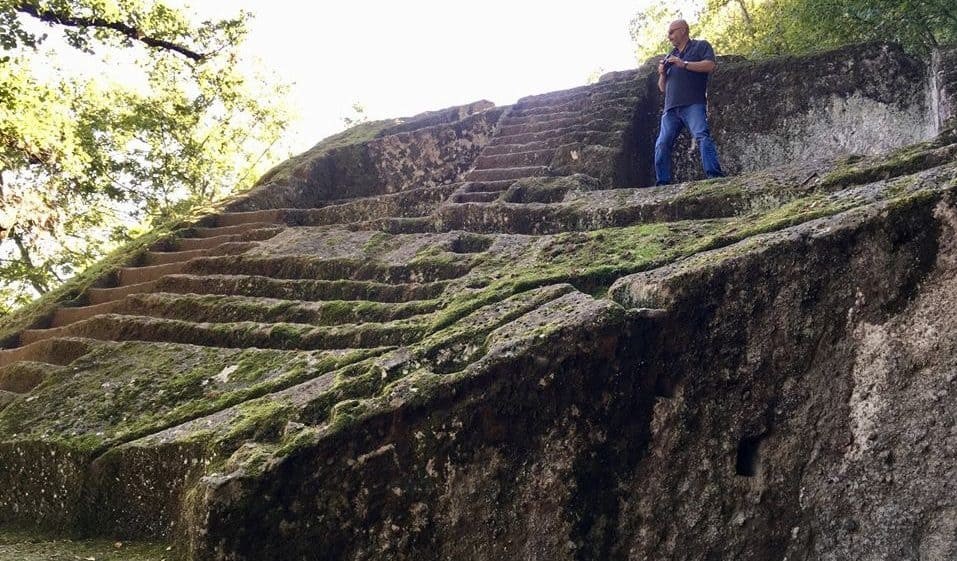

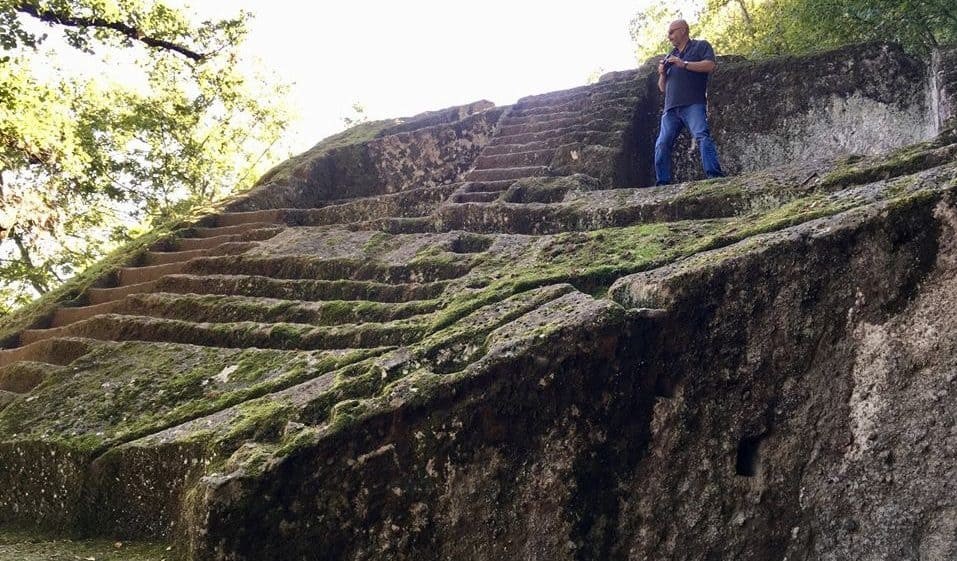

Jim H. standing in a platform near the angular right-front side. Photo: Historic Mysteries.

Etruscan builders carved the mysterious megalith from an enormous grey rock of volcanic tuff or “peperino.” It measures about 53 feet long, 24 feet at its widest point, and 30 feet tall. Three steep staircases cover the front face. There are 20 steps on the lower staircase, which lead to two minor altars. The two other staircases begin higher on the structure and have nine and ten steps respectively. These lead to the main altar on the rock summit. Along the angular edge, there is also a distinct canal that splits into two channels. These travel to the bottom of the rock. Cubbies scattered across the front and side faces may have held fence posts or votives.

A view of the canals and two minor altars of the Etruscan Pyramid of Bomarzo.

Who Were the Etruscans?

The Villanovans preceded the Etruscans and were the founders of the Etruscan culture. From about 1000 BCE, they appear to have developed a prominent presence on the Italian peninsula. This group preferred high hilltops for their villages, and many of those villages later became strong Etruscan cities.

Etruscans enjoyed an abundance of trade around the Mediterranean Sea as a result of their seafaring skills. They were adept and fierce warriors, and even the Romans adopted some of the Etruscan formations of battle. Additionally, beautiful art, pottery, architecture, and highly advanced metalwork were all trademarks of the Etruscan culture. They conquered a large portion of the Italian peninsula from the north-central to Southern Italy as far as Salerno. However, their fortune would not last. Eventually, by about the 1st century BCE, the Romans had conquered and absorbed the Etruscans and almost all traces of their culture.

Purpose of the Etruscan Pyramid of Bomarzo

The Pyramid of Bomarzo may have served different functions over time. The precise purpose is not clear. However, many experts believe that the megalith acted as an altar for pagan religious rites. For this reason, the site holds the nickname, “Stone of the Preacher.”

Mark Cartwright from Ancient History Encyclopedia explains in his entry on Etruscan Civilization that all aspects of life revolved around a large pantheon of gods. Amongst them, there was a god of the underworld, a god of the Sun, and a god of vegetation. The head god was Tin, while the god who sprang from the ground and brought them their religious text, the Etrusca disciplina (now lost), was Tages.

With such a multitude of gods, veneration and religious ceremonies were a full-time job. Etruscan life was filled with rituals such as the sacrifice of both animals and humans, reading of omens in the weather or birds, and predicting the future by looking at entrails or internal organs.

Ritual Sacrifice

Although we may never be certain about what took place at the Bomarzo pyramid, sacrifices of humans and/or animals for the sake of veneration or propitiation of deities were a common practice around the ancient world. Blood was a highly potent element during Etruscan religious rites and could give immortality to dead souls. There are a number of sacrificial depictions in Etruscan tombs.

One of the world’s highly respected authorities on the ancient Etruscans, Nancy de Grummond, indicates that although “Scholars have been reluctant to believe that the Etruscans practiced human sacrifice . . . Recent excavations in the monumental sacred area on the Pian di Civita at Tarquinia by the University of Milan (directed by M. Bonghi Jovino and G. Bagnasco Gianni) have proven once and for all that human sacrifice was indeed practiced by the Etruscans, through the discovery of a number of burials in this non-funerary context, of infants, children and adults” (de Grummond, AIA).

Drainage of Fluids at Temples

For the Etruscans, it was the responsibility of the living to provide the dead with the “sustenance” necessary for immortality. In one unusual tomb in Tarquinia, a child was inhumed rather than cremated. Deformities of his skull indicated that he probably suffered from epilepsy, which was a “divine disease.” Therefore, his seizures were divine messages directly from the gods. Near the child, there was an altar with a channel for sacrificial liquids that drained directly into a hollow in the earth. This alludes to a cult ritual ceremony possibly in the name of Tages, the boyish deity who sprang up from the earth to provide the religious scriptures. (Heimbuecher).

The Etruscan Pyramid of Bomarzo also contains channels, which may have provided efficient drainage of liquids during ritual sacrifices.

Such ceremonies as animal sacrifices, the pouring of blood into the ground, and music and dancing usually occurred outside temples built in honour of particular gods.

Mark Cartwright

Other Theories

The Etruscans would have certainly found the altar sacred. The pyramid lies in a northwest direction. This is where the Etruscan believed the Gods of the Underworld lived. The Etruscan God Satre also resides in the “dark and negative northwest region.” Satre would bring panic to the populace by throwing lightning deep into the Earth.

Finestraccia (Ugly Window)

A stone carving that looks like a chair sits at the entrance of Finestraccia.

As you make your way toward the pyramid, a striking stone structure lies on the left side of the path. Experts believe it once served as an Etruscan tomb which later became a dwelling. The exact age of this tomb is unknown, however, it may date to around the 7th century BCE like the pyramid. Perhaps it received the nickname Ugly Window because of the inaccurate proportions of the openings and door of the tomb. Additionally, a hole in the upper left corner of the tomb may or may not be a natural feature.

The Celtic Prince and His Opulent Tomb

Windows provided the inhabitant of this rock-cut tomb with fresh air.

The Finestraccia originally had two floors. The bottom floor contained the tomb and sarcophagus. The upper level consisted of living quarters or a storage area.

The tomb area of the Finestraccia.